|

Meet Josh Schonwald , a Chicago-based journalist and author of The Taste of Tomorrow: Dispatches from the Future of Food and listen to his book discussion on how people, trends and technologies are transforming the world of food. Chicago Tribune writer Bill Daley promises that this book is a fun read and writes, “Schonwald has the talent to explain serious, complicated issues in ways the average reader will understand. He does it in an entertaining, often irreverent way that keeps you turning the pages.”

Thursday, September 27 7:00 to 8:30 p.m. Friends of Ryerson Woods -- Brushwood 21850 N. Riverwoods Road Deerfield, IL 60015 This program is presented in partnership with the Lake Forest Book Store and Liberty Prairie Foundation. Books will be available for purchase at the event.

0 Comments

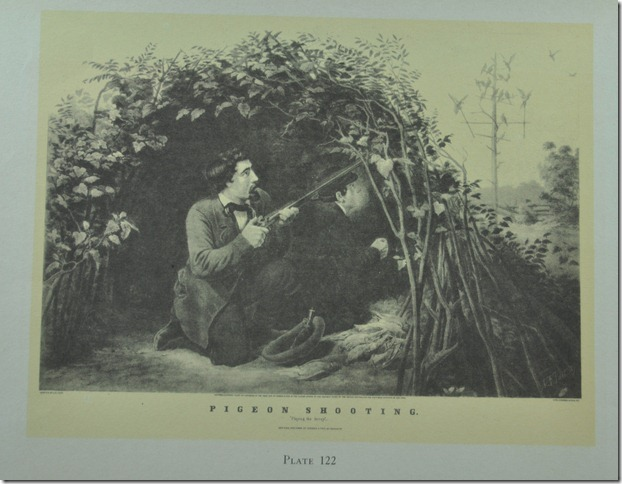

After being immersed in the literature of the passenger pigeon for going on three years now, I want to address a canard that was fueled by its inclusion in 1491. Although fossil remains have been found as far west as California, it would seem that the principal range of the passenger pigeon was a large region of eastern Canada and the United States, bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, the west by the headwaters of the Missouri River, the north almost to Hudson's Bay, and as far south as the gulf states. The bird's foremost scholar placed its population in 1500 as some where between 3 and 5 billion. The birds aggregated in flocks that would darken the sky for many hours at a time: when in Kentucky, Audubon noted a three day period when the masses of birds blocked the sun for the entire duration. As late as 1860, a single flight near Toronto likely exceeded a billion birds and maybe three billion. But due to unrelenting exploitation by humans for food and sport, they were virtually gone from the wild by 1900 and the last individual died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. A paper in 1985 by archeologist Thomas Neumann claimed that the absence of passenger pigeon remains in archeological digs demonstrates that the species existed in small numbers during prehistoric times due to predation and competition for food by Native Americans. It was only after Indian populations plummeted due to the diseases brought by Europeans were passenger pigeons able to attain historical abundance. This increase in pigeons was further helped by the reduction of deer, turkey, and other non-human competitors due to the appetites of the new arrivals. Unfortunately this assertion was stated as fact by Mann in 1491 and the popularity of the book spread the falsehood widely. It has resonated with many people who still support it even after learning that subsequent work has largely refuted it. I think a lot of people find reassurance in the idea that passenger pigeon abundance was due to Euro-American activities: the bird’s extinction at the hands of those same immigrants would somehow be less significant or awful. That we created the abundance exculpates us in our avarice that destroyed it.  Neumann, however, omitted many of the sites, including most of those mentioned above, where pigeon remains did appear. He also missed many of the earliest European descriptions depicting vast flocks of passenger pigeon. And finally, he greatly over estimated the degree and impacts that human competition and predation would have had on the pigeon population. For these and other reasons, archaeologists have largely repudiated this argument. A detailed refutation based on a comprehensive review of passenger pigeon remains in southern archeological sites is presented by H.E. Jackson of University of Southern Mississippi (“Darkening the Sun in their Flight: A Zooarcheological Accounting of Passenger Pigeons in the Prehistoric Southeast.” In Engaged Anthropology, edited by M. Hegmon and S. Beiselt. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology: 2005.) Professor Jackson’s work does suggest that pigeon numbers in the southeast began to rise during the period between 900 and 1000 AD, about 500 years before the appearance of Europeans. But even if this is true, the reasons for the increase are difficult to divine. Fortunately, though, we have the opportunity to learn more about the early history of the species. The Smithsonian and other institutions are currently extracting DNA from the toe pads of passenger pigeon specimens (there are over 1600 throughout the world) in an effort to seek insights on how the passenger pigeon lived and died. Joel Greenberg writes about natural history and has been most recently a principal in Project Passenger Pigeon, an international effort to use the 2014 centenary of the species’ extinction to help promote conservation. He is writing the first book on the bird since 1955. It is being published by Walker and Co., and has a publication date of January 2014. To learn more about the Gensburg-Markham Prairie, visit: http://www.chicagowilderness.org/CW_Archives/issues/summer2000/gensburg.html |

AuthorThis blog is written by the staff and partners of Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods Archives

February 2022

Categories |

|

21850 N. Riverwoods Rd.

Riverwoods, IL 60015 224.633.2424 [email protected] ABOUT BRUSHWOOD BECOME A PARTNER VOLUNTEER AND JOB OPPORTUNITIES |

Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods is committed to enabling the participation and enjoyment of our programming and events for all visitors. At Brushwood Center, you will have open access to accessible parking and entrance to the house, a gender neutral bathroom, and changing tables.

If you require certain accommodations in order to observe or attend our events, or have questions regarding accessibility of our facilities, please contact our Director of Public Programs and Music, Parker Nelson, at [email protected] or at (224) 633-2424 ext. 1. Programming and events at Brushwood Center are available to everyone, including but not limited to age, disability, gender, marital status, national origin, race, religion, and sexual orientation. Site Photography by: In Life Photography, Michael Kardas Photography, Ewa Pasek Photography, Brushwood Staff, and Josiah Shaw Productions |

OPEN TO THE PUBLIC Monday - Thursday & Saturday: 10am - 3pm Sunday: 1pm - 3pm and by appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed