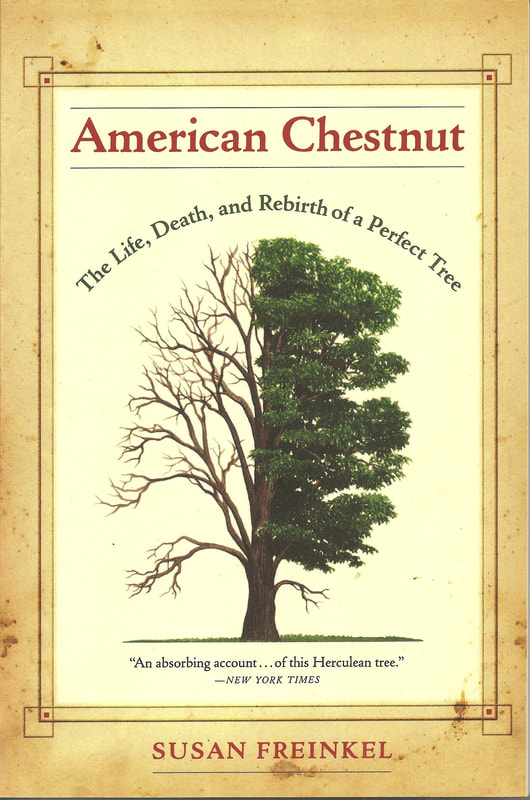

A post by Sophie Twichell, FRW's executive director: Tonight our RYERSON READS book group will discuss Susan Freinkel's American Chestnut: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree. I am looking forward to the group's discussion of this book, led by Professor Ben Goluboff of Lake Forest College. The group will explore this lost North American tree and the Chestnut blight that killed millions of trees in the first decade of the 20th century. The blight (a type of fungus) gained entry to this country on an imported chestnut tree from Asia, which Americans began bringing into the US in the late 19th century. The fungus could kill a mature tree in just 2-3 years. By mid-century, it was estimated that the blight killed between 3-4 billion trees! That's enough trees to fill nine million acres . . . enough to fill Yellowstone eighteen hundred times over. The book also assesses the blight's impact on forest ecology and human culture, as well as discussing the ongoing project to breed a disease-resistant Chestnut. Lots of good discussion material for tonight. Although the book explains in detail the measures taken to try to stop the blight, to develop disease-resistant trees and more, while reading I focused on imagining a landscape filled with wild chestnuts. You know how people ask, "if you could go back in time, who would you like to meet?" For me, it has always been "what would I have liked to have seen." My answer is "skies darkened for days by migrating passenger pigeons" or "millions of acres of uninterruped prairie" or "the migration of millions of American bison." I look at the landscape around me and try to imagine what it would have been like to be a part of it 500 years ago. This book added a new vision for me . . . witnessing wild chestnut trees filling the forests of Appalachia. The dominion of the American Chestnut tree sprawled over more than 200 million acres, spreading the length of the Atlantic seaborad and west to Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee. Unlike other parts of the world where the chestnut was a cultivated tree (a family with a chestnut orchard would never go hungry), here this tree was never tamed -- it remained a wild forest king. According to Freinkel, "legend has it that a squirrel could travel the chestnut canopy from Georgia to Maine without every touching the ground. Along the way it would pass over at least 1,094 places with chestnut in their names." Appalachia was defined by the chestnut, where they could account for as many as one in every four trees. Trees there were giants -- 12 feet wide and ten times as tall! Although the tree wasn't really ever formally cultivated for its nuts, people certainly gathered the nuts, which were sweeter than other types of chestnuts but also smaller (little acorn-size kernels that were difficult to peel). The trees produced nuts every year, and a single tree could bear as many as 6,000 nuts. Did you know that "nutting" parties were an annual autumn ritual in the cities and growing suburbs throughout the chestnut belt? "Not only country boys -- all New York goes a-nutting," observed Henry David Thoreau. Believe it or not, there was even a specific term, "chestnutting," for the collecting of the beautiful shiny, smooth nuts whose sweet flavor could be enjoyed raw, as well as boiled or roasted. Thoreau also wrote, "I love to gather them, if only for the sense of bountifulness of Nature they give me." The Cherokee protected their chestnuts by burning competing trees. The tree was the source of many remedies, including: tea for heart trouble or to stop the bleeding after birth, leaves for sores and as cough syrup, and galls to make an infant's navel recede. The Iroquois celebrated the chestnut tree in their story, Hadadenon and the Chestnut Tree. "Hadadenon lived alone with his uncle; the rest of the family had been killed by a group of seven evil witches. Their only food was a cache of dried chestnuts that was magically replenished at every meal. One day, Hadadenon foolishly destroyed the last of the magical nuts. His uncle cried that they would starve, so Hadadenon resolved to steal more chestnuts from a grove of trees jealously guarded by the seven witches. After many tries, he managed to get into the grove and take the nuts he needed, an act that broke the witches' curse and restored his family to life. Hadadenon gave each of his relatives a chestnut and told them to plant the seeds everywhere. The nuts, he declared, were a sacred food, to be shared forevermore with all who wanted them." The majesty of the chestnut was also captured in well-known poems, such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem published in 1841 The Village Blacksmith which begins "Under a spreading chestnut tree / the village smithy stands." Although not considered one of his major works, Robert Frost wrote a poem about the chestnut blight: Evil Tendencies Cancel Will the blight end the chestnut? The farmers rather guess not. It keeps smouldering at the roots And sending up new shoots Till another parasite Shall come to end the blight. Robert Frost (1936) To learn the status of the chestnut tree today, I hope you'll join our discussion tonight (7:30pm at Brushwood, $15 or $10 for FRW members) or read the book on your own. The selection of books for next season of RYERSON READS (our 9th season!) will be announced next week. Be sure to check our website at http://www.ryersonwoods.org/p/RyersonReads.html.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by the staff and partners of Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods Archives

February 2022

Categories |

|

21850 N. Riverwoods Rd.

Riverwoods, IL 60015 224.633.2424 info@brushwoodcenter.org ABOUT BRUSHWOOD BECOME A PARTNER VOLUNTEER AND JOB OPPORTUNITIES |

Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods is committed to enabling the participation and enjoyment of our programming and events for all visitors. At Brushwood Center, you will have open access to accessible parking and entrance to the house, a gender neutral bathroom, and changing tables.

If you require certain accommodations in order to observe or attend our events, or have questions regarding accessibility of our facilities, please contact our Director of Public Programs and Music, Parker Nelson, at pnelson@brushwoodcenter.org or at (224) 633-2424 ext. 1. Programming and events at Brushwood Center are available to everyone, including but not limited to age, disability, gender, marital status, national origin, race, religion, and sexual orientation. Site Photography by: In Life Photography, Michael Kardas Photography, Ewa Pasek Photography, and Brushwood Staff, Josiah Shaw |

OPEN TO THE PUBLIC Monday - Thursday & Saturday: 10am - 3pm Sunday: 1pm - 3pm and by appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed